The Lady’s Not for Turning

The Extraordinary Story of Mina Hubbard

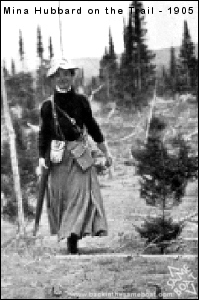

There were woodswomen long before “Woodswoman,” and one in particular stands out. In 1903, Mina Hubbard’s husband starved to death in Labrador. Two years later, his widow was leading an expedition along the same route, determined to finish the job her husband had left undone.

______________________________

by Tamia Nelson | November 12, 2002

Some of my happiest hours have been spent in library basements. Dark, dank, and neglected, they often house unexpected treasures: government reports describing the natural history of remote regions, bound volumes of nineteenth-century magazines, old books slated for “weeding” (librarians prefer to call this “de-accessioning”) … . What with one thing and another, trips into these dusty catacombs are always fascinating. Many turn into voyages of exploration among forgotten literary landscapes, with every shelf promising something new — and often delivering.

On one such expedition a few years back, I spotted bound volumes of Harper’s Monthly Magazine. Here was a find, indeed! Though not known as a sporting periodical — today’s Harper’s takes its job as a guardian of high culture very seriously — its turn-of-the-(last)-century counterpart occasionally printed articles about canoeing and kayaking. Ever hopeful, I lost no time in trying my luck. I reached for the volume stamped “1906.”

Fortune favors the bold. I slowly turned the pages of the big book, until, in the May number, I came to an article entitled “My Explorations in Unknown Labrador.” That sounds promising, I thought. And then my eye caught the by-line: Mina B. Hubbard. Mina. A woman’s name.

A woman explorer? In Labrador? In 1906? That was something I just had to read, and I did. What I found was a simple, unadorned tale of an extraordinary canoe trip. But while her tale may have been simply told, Mina Hubbard’s expedition through “unknown Labrador” lacked none of the elements of a good thriller. A simple tale, yes. But a tale of courage, loyalty, determination, and joy. Well worth a trip into the catacombs of the library to find. And like many extraordinary journeys, Mina’s had its roots in tragedy. In 1903, two years before she arrived in the Hudson Bay Company’s Northwest River Post on Lake Melville, her husband and two companions set out to …

…explore and map … the two large unknown rivers of the northeastern Labrador … [;] to witness the annual caribou migration … ; to visit … the Nascaupee Indians … ; and to secure the name … of being the first after [Hudson’s Bay Company trader John] McLean to cross the six hundred miles of unexplored wilderness lying between Hamilton Inlet and Ungava Bay.

It was a bold program, to be sure, even if the “unexplored wilderness” Mina’s husband was hoping to “be [among] the first to cross” was regularly traveled by Native hunters and trappers. But that wasn’t the worst disappointment in store for him. An unhappy conspiracy of poor maps, bad judgement, and worse luck sent the first Hubbard Expedition up the wrong river, and for Mina’s husband it proved to be the River of No Return. He died alone in his tent on the Susan River sometime after October 18, 1903. His companions were more fortunate. They survived — just.

Almost two years later, on June 27, 1905, Mina watched the Northwest River Post fade into the distance behind her canoe. She was determined to finish the job her husband had left undone, and her tenacity was rewarded. Exactly two months to the day after she left Northwest River Post, Mina and four companions, including a “Scotch Indian” named George Elson who had accompanied her husband, all of them traveling in two canoes, settled onto the mud opposite the Company post on the George River estuary, where they waited for the turn of the tide. Ungava Bay lay just to the west. They had no farther destination. The second Hubbard Expedition had achieved its ultimate north.

Of course, Mina’s accomplishment amounted to little more than a footnote in the history of exploration. True, she’d put much of Labrador “on the map,” and demonstrated conclusively that the “Northwest River” shown on an earlier survey by A.P. Low was a fiction. (The search for that will-o’-the-wisp had contributed to the failure of her husband’s expedition and his subsequent death.) But none of this amounted to much in the larger scheme of things. Early maps of the Canadian North were crisscrossed with non-existent or misplaced rivers. And other travelers would soon have corrected the error even if Mina had stayed at home in New York. Indeed, her husband’s second surviving companion, New York lawyer Dillon Wallace, left the Northwest River Post on the same day Mina did, also headed north. He made it all the way to the George River Post, too, though he arrived eight weeks after Mina. Whatever the fate of Mina and her party, therefore, “unknown Labrador” wouldn’t have remained unknown for long.

Nor could Mina lay claim to extraordinary feats of physical endurance. As was true of many nineteenth-century explorers, she neither wielded a paddle nor hauled on a line. Whenever her men portaged the canoes and gear, she walked the hills unburdened, encumbered only by an ankle-length skirt — worn over knickers — and a “long Swedish dogskin coat.”

What, then, did she do? She led. Her sextant established her party’s position on the map. Her revolver established her authority. The sextant saw frequent use, but the revolver remained in its holster. Mina apparently had the knack of command, and in George Elson she had an ideal subordinate. There was never any threat of mutiny.

This is remarkable in itself. At a time when European women were rare visitors to the North — the wife of the trader at the George River Post greeted her by saying, “Mrs. Hubbard, yours is the first white woman’s face I have seen for two years!” — Mina undertook to lead a party of men across a blank space on the map that had already claimed her husband’s life. And she succeeded. From beginning to end, her tale is marked by competence, good planning, and realistic expectations. There are no histrionics and no self-pitying asides. At the same time, though, Mina avoided the romantic hyperbole that mars so many expedition narratives. Instead, she frankly described the many hardships and discomforts of back-country travel:

Here the flies and mosquitoes were awful. It made me shiver just to feel them creeping over my hands, not to speak of their bites. Nowhere on the whole journey had we found them so thick … . It was good to escape into the tent.

A small matter? Yes. But anyone who’s ever traveled through the Canadian subarctic during “fly time” can attest that swarms of biting flies and other miseries can erode the resolve of even the most determined paddler. Mina never permitted such things to defeat her, though. The harrowing paragraph just quoted is followed immediately by this simple statement: “Next morning I arose early.” Mina obviously wasn’t a woman who gave up easily, and that was a very good thing. There was much worse to come. Not long after starting down the George River, Mina happened on a Montagnais camp. Only women and children welcomed her, however. The men were away, trading for supplies. Winter was coming soon, the women explained. And then an unexpected blow fell: Mina was told she had another two months’ journey ahead of her.

It was the worst possible news. Mina had not planned to over-winter in the North, and now she faced a terrible choice. Accept the well-meaning warnings of of the Montagnais women, whose local knowledge she was in no position to challenge, or trust to her sextant and map, a map which she herself had to correct as she traveled. There was no third way. She must either turn back and hope to get out before winter overtook her — the very same decision that had killed her husband — or continue on into the unknown. Forced to choose, Mina chose to believe in herself, her map, and her sextant. So the two canoes continued down the river, and ten days later they beached on the tidal mud. Mina knew then that she’d completed the journey her husband had begun.

There’s a lesson here for all of us, I suppose, women and men alike. The world has always been full of frightened people, anxious to lumber others with their fears. Take my father, for example. His outdoor experience was limited to one sleepless night spent at a state campsite with flush toilets. But that didn’t stop him from recoiling with horror when he learned of my early interest in climbing and canoeing. Experience be damned! My father knew what lurked in the wild dark, just outside the white circle of the streetlights. Terrible things. Dangerous beasts. Unspeakable horrors. So he put his foot down, hard, and planted it right on my dreams. At first, I tried to make him see things as I did, but when this effort failed, I gave it up as a bad job. I heard my father out, and then I went my own way. In the end, I lost a father, but I gained a whole new world in exchange. It was a better bargain than I’d dared to hope.

Perhaps that’s why I like Mina Hubbard’s story so much. It’s a simple tale, simply told. A story of courage, determination, and loyalty. Anticipating another resolute woman who came after her and put her thoughts into words — though in a very different context — Mina met the disheartening litany of well-intentioned nay-sayers with an unvoiced yet unmistakable reply: “You turn if you want, but the lady’s not for turning.” The rest is history.

______________________________

You don’t have to search through the musty volumes in a library basement to find Mina’s story. In 1985, Castle (a division of Book Sales, Inc., of Secaucus, New Jersey), reprinted “My Explorations in Unknown Labrador” — and many more nineteenth- and early twentieth-century articles, besides — in a handy volume entitled Tales of the Canadian Wilderness. The book’s out of print now, but it’s well worth a trip to a used-book seller to find a copy.